OUTBACK PEOPLE

Tunnel vision

Story Julie Miller

Photos John Denman

In political

circles, the title "elder statesman" is not lightly bestowed.

Mandela, yes. Whitlam - possibly the only local candidate. Clinton - not

in this lifetime. For the term implies more than just longevity and success.

It requires passion, a quiet conviction, versatility and endurance, and

a person who commands respect.

In political

circles, the title "elder statesman" is not lightly bestowed.

Mandela, yes. Whitlam - possibly the only local candidate. Clinton - not

in this lifetime. For the term implies more than just longevity and success.

It requires passion, a quiet conviction, versatility and endurance, and

a person who commands respect.

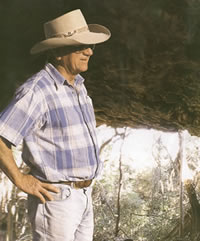

In the microcosm of Far North Queensland, a cattleman from the middle of

nowhere seems an unlikely contender. But that's exactly what Gerry Collins

is - an elder statesmen of the region's burgeoning tourism industry. With

his distinguished grey hair and proud bearing, he appears as comfortable

in a tuxedo as he does in a Driza-bone, and is as composed accepting an

award at a major function as he is leading groups of tourists through his

beloved Undara Lava Tubes.

For Gerry Collins, it depends which hat he's wearing - and he is a man

of many hats.

Just below the grasslands of the gulf savannah country near Mt Surprise

in

lie the spectacular Undara Lava Tubes, recognised by the scientific community

as the largest, longest and most important lava tunnels on the planet.

They began some 190,000 years ago when a major volcano blew its top, spewing molten lava into nearby dry river beds. The external lava cooled quickly, forming a crusty layer. But in the fiery realm of Hades, a fierce river of lava forged a path downstream, creating long, dark, hollow tubes. The outpouring of molten liquid was massive - covering 1550 sq. km of land.

After the insulated lava drained away, the legacy was a natural pipeline more than 100km long.

The lava from

the Undara volcano travelled 164km to create the longest lava flow from

one single vent in modern geological time.

The lava from

the Undara volcano travelled 164km to create the longest lava flow from

one single vent in modern geological time.

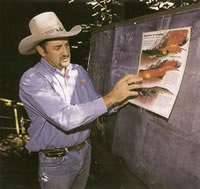

Some of the tubes are still fully enclosed, dark and eerie caverns feared

and shunned by local Aboriginal tribes. In some parts, however, the ancient

roof has collapsed, creating fertile pockets of rainforest where rare species

of plants, animals and insects now thrive - euros, rock wallabies, bettongs,

bats, cave moths and the birds of the night that flock to gorge on them.

It's a delicate, finely balanced environment, untouched for thousands

of years, a veritable buried treasure. Today, the lava tubes are protected

by the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, which allows public access

under supervision of savannah guides from the Undara Experience - the people

who know this land best. ![]()

Full story: Issue 20, December 01 / January 02